We are less than week out from the local and European elections, and things are changing rapidly. The campaign period has brought a significant change in polling – while the overall trends have remained the same, the rate of change has become a lot sharper. Sinn Féin’s position is declining rapidly, with all three major polling companies indicating that their support is below their 2020 total, Fianna Fáil continue to regress, Independents/Others are rising, and there are the first signs of progress in a very long time for Fine Gael.

So what does this mean for the upcoming elections? I will try to cover the Europeans before polling day, but for now, let’s focus on the local elections. I have looked at this before, while concluding that concrete assumptions cannot be drawn from the information we have. We now have much better information – updated polling, a full list of candidates and even some very limited LE specific polling, but that caution and all caveats I expressed at the time remain very much the same.

In that prior post I still referred to what I was doing as “projections” which, as I expressed at the time, it wasn’t really, but I couldn’t think of a better way to articulate it. I have now got a better word to describe it – “benchmarking”. We’ll come to what I mean by that in a moment, but I’ll talk about how this was measured first.

Contents

Methodology

The broad methodology used is the same as for the general election, but with some nuances. The support parties have is adjusted for current polling averages per region, which is then applied to local elections, using the difference between the election results and the current polling to measure swing. However, given that GE polling does not necessarily map to local votes, and that we do have a specific local election section in the latest poll from RedC, I have opted to produce two sets of benchmarks – one based on the GE polling, and one based on the RedC poll.

The other difference here is the most extensive piece of transfer analysis I have ever produced. This involved accumulating all of the transfer data from the 2019 local election – tens of thousands of data points – to build the most comprehensive view of transfer patterns in each and every LEA in the country. These were then applied to current candidates, using Local Authority, regional or national averages to fill gaps. It’s not perfect, and it was honestly a horrible experience – every time I close my eyes I see spreadsheets – but I think it gives a much better indication of potential outcomes than the previous work on local elections did.

Finally, as there are a lot of new parties and an increased number of candidates, vote splits within parties and support levels for new candidates were calculated using a combination of historical data and patterns within the local authority. Again I would point out that this is not perfect, particularly when it comes to Independents and new parties, but I think it is the closest we can get to producing something that captures the general shape of things.

What do I mean by “benchmarking”?

I want to take a brief moment before we go further to talk about why I refer to this as “benchmarking” rather than “projections” or anything else, and what I mean by that.

I think our capacity to make a projection on local areas is limited. The data we have is at a much higher level; an LEA will be far removed from regional or national polling, and the closer you go down, the more variance you will see. The dynamics at local level can be very intense and idiosyncratic, and while they do tend to reflect broad trends, they can be a lot more swingy and prone to throwing up results that, to an outsider, might look bizarre, but make sense within that area.

So, “benchmarking” – I think it’s very important we don’t take this as a statement on what will come. Rather, this exercise is about saying that we have this polling data, and here’s what it would look like when we apply that to the election. Not “here is what the parties will achieve”, but “here is the line at which a party will be under- or over-performing relative to the implied result from polling“. All the usual cautions about interpreting polling apply here, of course, but essentially this is a measure of the utility of the polling itself as well as the performance of the parties.

Therefore, while in aggregate things are probably a reasonable reflection of what expectations should be, at the LA level – or worse, the LEA – I would be extremely skeptical of any claim expressing predictive value. Last time I published a breakdown by LAs; this was done out of interest and with the caveat that it shouldn’t be viewed particularly seriously. I won’t even do that this time; from going as deep into the data as I did, while I don’t think it’s particularly inaccurate considering the purpose of this exercise, I think it could easily be misunderstood, or misrepresented in order to mislead as to what it is actually saying.

Caveats

This wouldn’t be one of my posts without a massive list of caveats, so, here we go. I have outlined already above some of the challenges when it comes to local elections, but I think it is important to fully outline these so anyone reading has an honest understanding of what they are looking at.

- As above, local dynamics can be obscure to people outside of them, and do not reflect well in data. Additional caution is required when using LA or other averages to fill gaps.

- Two parties – the Social Democrats and Aontú – have had growth since 2019 that while small in absolute terms, is very significant in relative terms. Thus this kind of benchmarking sets higher-than-expected watermarks for both

- Independents and new parties are extremely variable and historical data has more limitations than with established parties. They have to be grouped together an ordered with a degree of arbitrariness, hence why they are presented as a pool rather than broken down further.

- Candidate specifics also matter a lot, and even in small LEAs, geography can have tremendous impact on transfers, particularly for the bigger parties and Independents.

- Transfers may change, not just because of candidate composition and geography, but also because Ireland has historically seen some fairly incoherent patterns across ideological lines. Given the current political atmosphere, transfers could end up being more ideologically aligned than in the past.

- Candidate vote splits are also based on historical patterns, but this can vary in unexpected ways, and there are definitely vote splits in the data that could flip seats if managed better or worse than 2019, even if the party’s total vote is the same.

- And finally, and perhaps most importantly – remember that polling can change in the final week of the campaign. We have already seen significant changes over the last few weeks, these may continue, stabilise or reverse – this is particularly true for the figures in the RedC poll.

Results

With that out of the way, let’s get into the results. There are two benchmarks here, as mentioned above – one based on GE polling, and one based on the RedC poll. Both have their pros and cons and, again, neither should be taken as predictive, but as an indicator of whether a party is over- or under-performing the outcome indicated by the polling data.

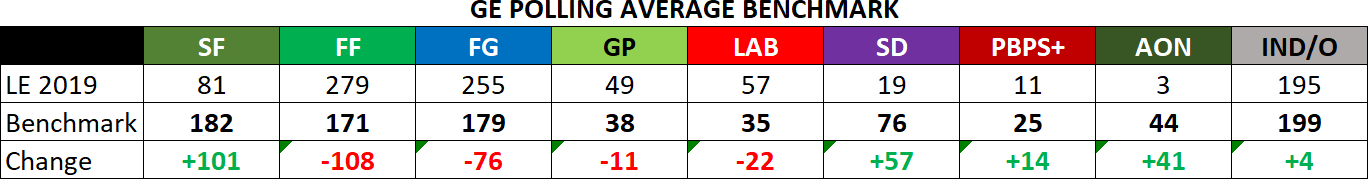

First, the benchmarks based on the general election polling average. These are, I think, probably the less spicy of the two, showing a fairly even distribution between Sinn Féin, Fianna Fáil, Fine Gael and Independents/Others, which broadly tracks with what one might expect from current polling (and given that Ireland’s political geography tends to favour Fianna Fáil slightly relative to their current vote share).

Using GE polling has obvious downsides – it’s well established that a significant portion of people have different preferences between different types of election, and the polling average will move slower than the rapid changes we have seen recently. On the plus side it does offer a broader look with the most available data and, most interestingly, can highlight the gap between local and national trends. If there is a significant difference between this and the eventual outcome – which there might well be – that itself is potentially useful information.

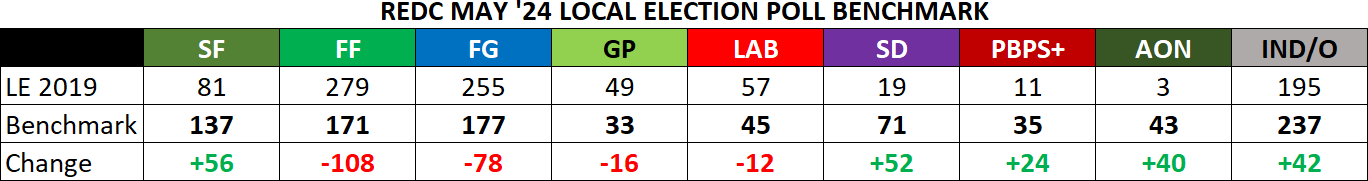

This next set of benchmarks uses the May 2024 RedC poll regional data for the segment done on the local elections. This is a lot more interesting, and despite them making significant gains versus their catastrophic 2019, would be a very disappointing result for Sinn Féin. Interestingly, the Fianna Fáil and Fine Gael figures line up very closely with the GE benchmark, but the seats are distributed very differently – this is that aggregating effect I mentioned earlier.

Of course this is also not perfect. This is a single poll that gives us a much more limited sample size and is therefore more vulnerable to error or outliers – the level of support for PBP in Dublin, for example, is very unusual. That’s not to say it is going to definitely be wrong, but it should be borne in mind when looking at this. On the plus side, it does give us a response on the specifics of people’s local election preferences – and even in the sample itself, there are clear differences between local, general and European, which is valuable.

Once more I will emphasise that this benchmark only compares results to the expected output from a single poll and should be interpreted in those terms, not as a predictive statement or projection.

Analysis

So, what conclusions can we draw from this? If you’ve read the whole way through this piece, you’ll not be surprised to hear me say “very few”. But I can offer some notes on why we are seeing some of these results for the smaller parties, and what it might mean if parties land in and around either of these benchmarks.

Firstly, on the results themselves, I want to get this out of the way first – why are the Social Democrats and Aontú so high? I did allude to this above but I want to discuss in a bit more detail. I’ll be quite clear that I don’t personally think it’s realistic to expect the SDs to return 90%+ of their candidates. Aontú getting 2/3rds of their returned is perhaps slightly more plausible, but also an enormous stretch. So why does the benchmarking show this?

Basically, both parties were much smaller in 2019 than they are now, in terms of both polling levels and numbers of candidates. Given their relatively low levels, this creates very significant polling swings, and can cause additional challenges where they are running in new areas. If a party is suddenly doubling or trebling its vote share, that can cause anomalies to occur. There are two reasons I haven’t “corrected” for this: firstly because absent historical data for these two parties, it’s not clear how to “correct” it – this election will help establish that. Secondly, because I think it is useful to demonstrate the gaps between pure data approach and what may happen on the ground. To combine both of these, this entire broader projection project is iterative, it has failures and misses and being able to find these polling gaps is tremendously helpful in making it work better in future.

That said, with the way polling in general is pointing, both should gain a significant number of seats in this election and ought be bitterly disappointed if they don’t.

Independents and Others isn’t broken down for reasons outlined above, and there are as always more challenges modelling for them, but all polling points to a positive day across the board. How this is distributed is a more open question and one to which we do not have sufficient data for an answer. Also something that can’t be derived from data is candidate quality, which matters massively here. More “good” candidates could well result in this diverse grouping going well above the benchmark, and vice versa.

I have no way of knowing who is considered “good” or “bad” in the vast majority of locations, so this overall leans heavily on historical data, allowing more precision to be afforded to people who have run before. For example, let’s imagine an LEA where IND/Oth got 10% of the vote in 2019, and one of them got 70% of that (i.e. 7%). Their base vote would then be assumed to be 70% of the IND total for whatever the figure in the LEA is in 2024. Again, imperfect, but it does attempt to account for people who have shown themselves to be strong or weak in the past.

Outside of that the ordering of Independents/Others is, by necessity, somewhat arbitrary, even more so in the places where there are vast numbers of them running. I am not going to offer any kind of detailed breakdown, but to satisfy curiosity I will say that the following “Other” parties were shown as being able to hold or win seats under both benchmark models: Independent Ireland, Right2Change, Rabharta, Workers’ Party, Independents4Change, Kerry Independent Alliance, 100% Redress, Independent Left, Republican Sinn Féin, Irish Freedom Party, Wexford Independent Alliance, and the Workers and Unemployed Action Group. This list has zero value even as a benchmark, because a lot of this ordering is arbitrary with non-incumbents, but I have put it here to demonstrate the sheer diversity of what is captured by the “Other” grouping.

Then, on what this means. For Sinn Féin, this is a problem. The two benchmarks reflect their polling decline, one much more severely than the other. The first one would be merely frustrating – still the biggest grouping but by an incredibly narrow margin. The second, however, would be a significant disappointment – failing to overtake FF or FG would be a very real manifestation of their polling implosion, and should result in a period of reconsidering their strategy and approach. It can be turned around – SF turned their rotten 2019 into a glorious 2020 – but it won’t happen by magic. Which benchmark SF end up closest to could have significant influence on how they approach the next GE.

For Fianna Fáil and Fine Gael, this is much as ought be expected. Both parties are polling worse than in 2019, and a number of seats that were kind of picked up through a lack of other options may be under pressure with more expansive strategies from other parties. Both also have, historically, serious problems with transfer leakage at local level – if that improves in this cycle they could both handily beat the benchmarking. But unlike SF, I think these parties are prepared for a lower result than in 2019. If either of them do emerge the biggest party (excepting Independents), they certainly will try to sell this as a triumph and an endorsement of government, even if they suffer a significant loss of seats.

That, like SF’s position, is the paradox of these elections – because of the expectations set by the general election and the years of polling that followed it, we are in a place where a party that gains seats will be considered to have failed, and parties that lose seats will be able to declare a victory of sorts. And, given where it looked like we would be two years ago, it’s not entirely wrong if they do.

On a final note, to expand on this a little, the benchmarks reflect something we often miss, something about the long view, something I had not even really thought about much myself with all the immediate change in front of us.

Much has been made of the polling decline of Sinn Féin, and it’s justified. But if we go back to before the last general election, to the 2019 local election, it’s Fine Gael and Fianna Fáil who stand to lose the most ground. History does not take place over one election cycle. There is much that can change in future, and there are so many factors that go into shaping it. And nobody is psychic, nobody knows for sure what it will look like, and anyone telling you they are 100% sure of what will definitely happen a year from now is either a fool, or takes you for one. Always, always, always bear that in mind when reading any kind of political coverage or analysis.

Anyway. Go vote. Unless you’re planning on voting for a fascist, in which case I hope you get stuck up a tree and the fire brigade can’t rescue you until Saturday morning.

*****

Thanks so much for reading! This website is done entirely in my spare time and run without ads, so if you want to donate, please do so via Patreon or Ko-Fi – any support is greatly appreciated and 100% of any donations received are invested into the costs of running and improving the site.